The doubling of the NIH budget between 1998 and 2003 affected nearly every part of the biomedical research enterprise. The strategies we use to support research, the manner in which scientists conduct research, the ways in which researchers are evaluated and rewarded, and the organization of research institutions were all influenced by the large, sustained increases in funding during the doubling period.

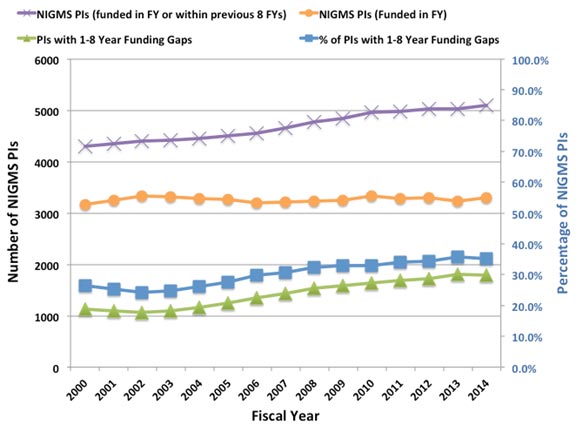

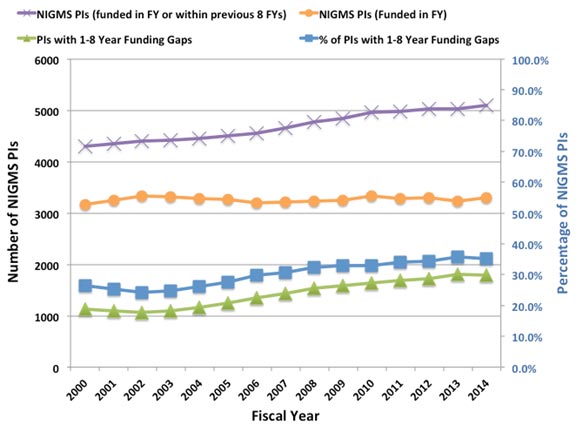

Despite the fact that the budget doubling ended more than a decade ago, the biomedical research enterprise has not re-equilibrated to function optimally under the current circumstances. As has been pointed out by others (e.g., Ioannidis, 2011; Vale, 2012; Bourne, 2013; Alberts et al., 2014), the old models for supporting, evaluating, rewarding and organizing research are not well suited to today’s realities. Talented and productive investigators at all levels are struggling to keep their labs open (see Figure 1 below, Figure 3 in my previous post on factors affecting success rates and Figure 3 in Sally Rockey’s 2012 post on application numbers). Trainees are apprehensive about pursuing careers in research (Polka and Krukenberg, 2014). Study sections are discouraged by the fact that most of the excellent applications they review won’t be funded and by the difficulty of trying to prioritize among them. And the nation’s academic institutions and funding agencies struggle to find new financial models to continue to support research and graduate education. If we do not retool the system to become more efficient and sustainable, we will be doing a disservice to the country by depriving it of scientific advances that would have led to improvements in health and prosperity.

Re-optimizing the biomedical research enterprise will require significant changes in every part of the system. For example, despite prescient, early warnings from Bruce Alberts (1985) about the dangers of confusing the number of grants and the size of one’s research group with success, large labs and big budgets have come to be viewed by many researchers and institutions as key indicators of scientific achievement. However, when basic research labs get too big it creates a number of inefficiencies. Much of the problem is one of bandwidth: One person can effectively supervise, mentor and train a limited number of people. Furthermore, the larger a lab gets, the more time the principal investigator must devote to writing grants and performing administrative tasks, further reducing the time available for actually doing science.

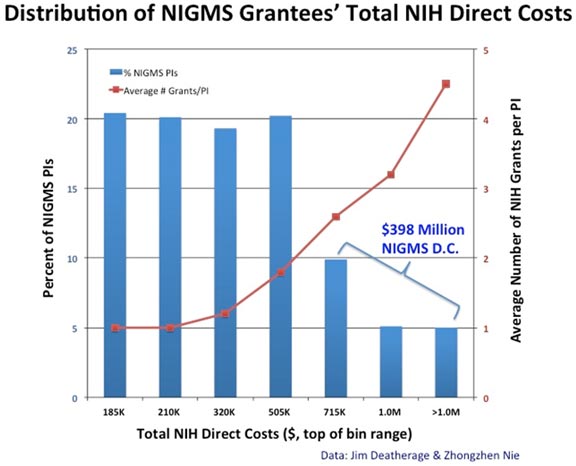

Although certain kinds of research projects—particularly those with an applied outcome, such as clinical trials—can require large teams, a 2010 analysis by NIGMS and a number of subsequent studies of other funding systems (Fortin and Currie, 2013; Gallo et al., 2014) have shown that, on average, large budgets do not give us the best returns on our investments in basic science. In addition, because it is impossible to know in advance where the next breakthroughs will arise, having a broad and diverse research portfolio should maximize the number of important discoveries that emerge from the science we support (Lauer, 2014).

These and other lines of evidence indicate that funding smaller, more efficient research groups will increase the net impact of fundamental biomedical research: valuable scientific output per taxpayer dollar invested. But to achieve this increase, we must all be willing to share the responsibility and focus on efficiency as much as we have always focused on efficacy. In the current zero-sum funding environment, the tradeoffs are stark: If one investigator gets a third R01, it means that another productive scientist loses his only grant or a promising new investigator can’t get her lab off the ground. Which outcome should we choose?

My main motivation for writing this post is to ask the biomedical research community to think carefully about these issues. Researchers should ask: Can I do my work more efficiently? What size does my lab need to be? How much funding do I really need? How do I define success? What can I do to help the research enterprise thrive?

Academic institutions should ask: How should we evaluate, reward and support researchers? What changes can we make to enhance the efficiency and sustainability of the research enterprise?

And journals, professional societies and private funding organizations should examine the roles they can play in helping to rewire the unproductive incentive systems that encourage researchers to focus on getting more funding than they actually need.

We at NIGMS are working hard to find ways to address the challenges currently facing fundamental biomedical research. As just one example, our MIRA program aims to create a more efficient, stable, flexible and productive research funding mechanism. If it is successful, the program could become the Institute’s primary means of funding individual investigators and could help transform how we support fundamental biomedical research. But reshaping the system will require everyone involved to share the responsibility. We owe it to the next generation of researchers and to the American public.

Figure 1. The number of NIGMS principal investigators (PIs) without NIH R01 funding has increased over time. All NIGMS PIs are shown by the purple Xs (left axis). NIGMS PIs who were funded in each fiscal year are represented by the orange circles (left axis). PIs who had no NIH funding in a given fiscal year but had funding from NIGMS within the previous 8 years and were still actively applying for funding within the previous 4 years are shown by the green triangles (left axis); these unfunded PIs have made up an increasingly large percentage of all NIGMS PIs over the past decade (blue squares; right axis). Definitions: “PI” includes both contact PIs and PIs on multi-PI awards. This analysis includes only R01, R37 and R29 (“R01 equivalent”) grants and PIs. Other kinds of NIH grant support are not counted. An “NIGMS PI” is defined as a current or former NIGMS R01 PI who was either funded by NIGMS in the fiscal year shown or who was not NIH-funded in the fiscal year shown but was funded by NIGMS within the previous 8 years and applied for NIGMS funding within the previous 4 years. The latter criterion indicates that these PIs were still seeking funding for a substantial period of time after termination of their last NIH grant. Note that PIs who had lost NIGMS support but had active R01 support from another NIH institute or center are not counted as “NIGMS PIs” because they were still funded in that fiscal year. Also not counted as “NIGMS PIs” are inactive PIs, defined as PIs who were funded by NIGMS in the previous 8 years but who did not apply for NIGMS funding in the previous 4 years. Data analysis was performed by Lisa Dunbar and Jim Deatherage.

UPDATE: For additional details, read More on My Shared Responsibility Post.