In a recent post, I described initial steps toward analyzing the research output of NIGMS R01 and P01 grants. The post stimulated considerable discussion in the scientific community and, most recently, a Nature news article.

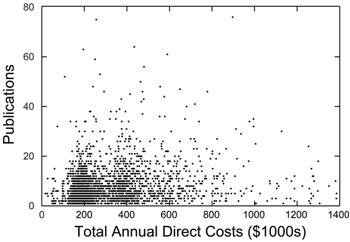

In my earlier post, I noted two major observations. First, the output (measured by the number of publications from 2007 through mid-2010 that could be linked to all NIH Fiscal Year 2006 grants from a given investigator) did not increase linearly with increased total annual direct cost support, but rather appeared to reach a plateau. Second, there were considerable ranges in output at all levels of funding.

These observations are even more apparent in the new plot below, which removes the binning in displaying the points corresponding to individual investigators.

I’m no fan of the GlamourMag thing but I just don’t see where the policy outcome of these analyses can work* without recognizing that a typical GlamourMag pub is *hugely* more expensive on a per-pub basis and that bigger, more well-funded labs are going to be disproportionately in the Glamour game.

Nice that we have the data to discuss, though. Kudos, as usual.

*now, if you are using this to try to break the back of the GlamourPub game then rock on…

Drugmonkey’s comments are very true. The gap between publications in specialized journals (impact factor 13) or general interest journals (impact>25) in terms of quantity, quality, innovation, and significance is HUGE.

This may be too bold a statement but in my field I estimate that a lab aiming for one impact >13 paper could aim lower and instead get 10 or more papers in specialized journals. In my opinion the smaller papers are of limited value, often ignored and a waste of tax payers money.

Clarifying mistype in post above:

specialized journal = impact 13

general interest journals= impact> 25

This indicates a breathtaking ignorance of the history of science in general, and life science in particular. A single example: what journals were the original papers on the ubiquitin system (Hershko and colleagues) published in? Answers: Not Science; Not Cell,; Not Nature. I can readily think of dozens of similar examples from many disparate fields. Conversely, it’s easy to reel off a list of S/N/C papers that sunk like stones, or were just plain wrong.

As noted above by my esteemed colleague DrugMonkey, “publication” isn’t a useful measure of output, due to the variation you display above. Publication * readership (including, but not limited to number of citations) of that publication would be a more useful metric.

Yes, use publication* readership as the metric. Then you can simplify the NIH grant review process. Just award money to whomever has the highest publication*readership count.

Even better you can demand that all investigators read twice as many papers each year to double your overall publication*readership count.

Then you can go to congress and demonstrate how you have increased the impact of funded research and maybe even suggest a new Institute: the National Institute of Publications.

Come on, we want to live a long comfortable life. We want to spend our money on leisure and luxury items, not healthcare. Don’t lose sight of the real targets here.

Being able to focus money on the more important research as opposed to spreading it around randomly would generally be expected to lead to less spending on healthcare, and would be a more efficient use of taxpayer dollars, too.

So would public access to publicly funded research, come to think of it.

Actually, open access is a very INEFFICIENT use of taxpayer funds: they require that the taxpayers pay for open access through an author pays model, even though there are millions of taxpayers that never asked for or chose to use their tax dollars in that way. Conversely, in a subscription model, only those users that wish to purchase a certain journal do so, using their scarce resources as they see fit. Should that journal not deliver in value, the subscribers will vote with their wallet to not subscribe. In an author pays model, journals have little incentive to keep journal “prices” to authors low, since they’ll be paying with a third parties funds (ie. the taxpayer), so I surmise we’d likely see prices rise until the NIH interjects and caps the fee journals may charge authors. In essence though, an author pays model: decreases discrimination and choice, therefore decreasing efficiency.

anon – You might want to look at how library subscriptions actually work these days. First of all, the majority of Open Access publishers charge no author-side fees at all. Second, toll-access publishers also charge page charges equivalent to Open Access author-side fees. Third, subscriptions are bundled together and sold to universities as part of a package deal not unlike Cable TV subscriptions, where to get a subscription to a desirable journal, you must also pay for a subscription to a whole bunch of others that you may not want.

While I share your concerns about efficient use of resources, policy recommendations should be informed by a basic level of understanding of the facts. Journal prices under the current system have risen much faster than inflation over the past 30 years, because they’ve been awarded a monopoly on distribution of research results. Open Access provides competition for attention, which is the real currency these days. You want efficient use of your tax money? How about we use money allocated for research on research, not buying Ferraris for publishing company executives?

Hmmmm…not sure where to begin with this. First, comparing the cable TV market to journals is just wrong. One is an oligarchy with massively restrictive regulations and start up costs (I know you’re tempted to think I’m talking publishing, but I’m not). The other is a market that is characterized by a few large players, and hundreds of smaller, mostly non-profit players. The few large players derive their value from the increased demand by their customers. Journals have no intrinsic value. It is not like a commodity that is superior to others, and therefore sees increased demand. The Cal-wide boycott of Nature is a step in the right direction. It’s like blaming the tulip bubble on the tulips! Although I know you don’t want to hear this, but you have a choice. And more power than you realize. University faculty could easily mobilize to steer quality articles away from high demand journals. It would border on anti-trust issues, but it could be done to alleviate demand and decrease prices. But people keep rushing to these few journals. Also, journal prices have gone up in direct correlation with the doubling of the NIH budget. More science = more demand. But the problem has been exacerbated by every researcher submitting to a few key journals. Look at non-profit journals – you don’t see nearly the increases that you see in the Chosen Few.

Thanks for this lively discussion, but it’s getting off topic. If you’d like to continue the thread, please be sure your comment is relevant to the post’s main point.

That funding at the top levels corresponds with a plateau in output I think is expected. Larger grants allow investigators to go after bigger questions that take longer to answer, but are often more impactful to the scientific community. I think the density at the lower funding levels is perhaps an illustration of PIs grabbing the low hanging fruit in order to compete in the next funding cycle. Labs living paycheck to paycheck if you will.

In addition to the “glamour mag” issue raised by DrugMonkey, there is also the issue of field specificity in the relationship between publication number and “productivity”. Some fields demand a much greater diversity and number of experiments in each paper, while other fields are comfortable with papers describing a single observation.

I completely agree that simply counting publications is a poor measure of output. Using these kinds of metrics only encourages incremental publications and other forms of literature pollution.

It may be difficult to do, but this plot would be more meaningful if the overall impact of the publications (# x journal impact factor) was related to total NIH funding.

Jad, How very charitable is your assessment of the plateau in output from larger labs/grants! However, from my observations the lower output in large labs isn’t because of some lofty pursuit of cutting edge science, but rather because large labs are unwieldy, inefficient, and poorly managed. There is limited intellectual territory and the workers are all trying to find their unique angle on a sparse landscape. The PI, being pulled in multiple directions doesn’t recognize a portion of the members of his own lab, but the machine lumbers forward, spewing out product. On the larger issue of “productivity”, I would use citations as the metric, NOT # of publications, as people churn out any number of meaningless pubs to up their numbers, with little or no impact on the scientific endeavor.

Citations as a metric have been well and truly gamed, almost to the point of uselessness. People cite papers they’re criticizing, using methods from, or just to flatter someone. The attention paid to a paper is a better measure of the impact than who cited it, if only because it takes years for a paper to come out and start to accumulate citations.

Fair enough. Citations are imperfect. “Attention paid to a paper” as you say may be a better metric. How do we assess “attention paid to a paper”?

If I may be so bold as to suggest it, here’s an example: (no longer available)

On the left, next to the title, is an indicator of the people who are reading that paper, who have given it tags, etc. Surely this is a good start?

The idea that the labs with the largest support are those going after the most important, most fundamental problems is ludicrous. NIH support is disproportionately directed at applied medical research, and this is true now more than ever because of translational research. As Ed points out, it’s hard to run big labs efficiently and a lot of work winds up directed by postdocs. The best funded groups I know are focused on relatively narrow problems with low long term impact but high medical relevance and high short term impact. They are, by the way, very good at what they do, but what they do isn’t really directed at producing major breakthroughs. If your technicians and postdocs testing compounds against a target in hopes of getting a drug lead, you aren’t going to produce ground breaking science.

Most project grants, just like forced marriage, do not work as well as R01 because they were driven by money, rather than personal scientific interest. Your data reveal the simple relation between competitiveness in obtaining grants and efficiency of producing results. Larger grants tend to be less competitively obtained, more poorly managed, and less productive. Shifting more money to R01 is the way to go.

The data that I presented are for NIGMS R01s and P01s with the P01 contribution broken down in subprojects. No other large mechanisms are included. R01s account for more than 90% of funding reported in this analysis.

It would be interesting then to compare regular R01 and P01 subprojects. I suspect that P01 subprojects would have less output.

It is a serious mistake to conflate the “most important” problems or the “best science” or some other nonsense with the impact factor of the journal in which it is published.

My point was merely that if you condition on labs publishing (or seeking to publish) in Science or Nature then you are going to have a lot more in direct costs being pumped into each resulting publication. Particularly when you consider all the dead ends, abandoned projects that got scooped (and are therefore no longer of interest to the GlamourPI).

How much valuable work is sitting on someone’s desk right now as they polish it so that it can spend years going through the publication process to maybe finally one day end up in Nature or Science? Wouldn’t it be better to capture all that stuff, with pre-publication peer review to maintain technical integrity, so that we don’t have these huge time delays? Especially now that we have effective mechanisms for doing some of the filtering post-publication?

The title of your piece in today’s email links “Impact” and “Output” with number of publications (“Another Look at Measuring the Scientific Output and Impact of NIGMS Grants”). I’m sure you’ve heard this from others, but equating impact with the number of publications is so obviously a false proposition that I don’t know where to start. Any researcher could generate as many publications as you want by sending the minimal publishable unit to some horrible journal. I’m guessing that’s not what NIGMS wants, but if you keep publishing that plot, that’s what you’ll encourage.

I am in favor of assessing impact, but this particular plot is so overly simplistic, with so many caveats and legitimate alternative explanations, that I would suggest that it is at least meaningless in measuring impact, and potentially misleading to funding policy. I’m not sure what the goal is here, but if it’s to say that large grants are not a good use of money, this is not strong evidence. For example, “cutting edge” research is often expensive, and yes, horribly inefficient. Just for a simplistic example, you might burn through 10 projects to hit the one that makes a true advance. So you could choose to make 1 real advance with that money, or fund 10 “safe” projects that all result in a bunch of publications of less significant, incremental work. I would argue the research most worth trying fails most of the time.

I agree completely with your statement that simply counting publications is a poor measure of scientific impact. NIGMS funding policy does not depend in any simple way on counting publications. The purpose of these posts is to stimulate discussion of various approaches to assessing scientific impact, a very important and challenging problem.

It seems that more than a few of you are missing the point, being focused too much on the axes rather than the trendline.

Based on the plot and other data from Dr. Berg, Ockham and common sense say that any metric you choose for “quality” of output will likely show poor correlation with NIGMS funding to the PI. These data suggest instead that funding a PI above $2-400k from NIGMS yields a diminishing rate of return.

(Of course there are any number of confounding factors skewing the distribution and affecting any individual datum. There may be better metrics. However, publications do correlate with other markers of output or impact. Few colleagues are considered productive who publish very few papers, irrespective of their quality. Indeed, when they are discussed in a grant panel, it is often as the exception to the rule. Given all that, how about we drop all the arguments about impact factors, etc., and just consider the meaning.)

So, if there were little correlation between investment and output, should we care? Should we act on it? Well, R01’s are funding at less than 20%. The data provide a quantitative rationale for further spreading the money around instead of concentrating it in fewer hands. If you are concerned about the sanctity of review, NIGMS placing a firm limit on funding to a PI is an easy way to improve the payline without injecting funding into the priority score.

IMHO: When and if the NIH is back on a better footing, we might have the luxury of reaping the possible “benefits” of generous funding of some PI’s. As of now, with recently thriving labs led by mid-career colleagues starved for funding, this overfunding of individual labs is destructive and the money should be redirected to the best science in other labs.

These data show that a plurality of labs are productive on a single R01. Extrapolating a bit, I would conclude that many research groups are very adept at extracting maximum value from limited research funds. This could be key to an approach to expand the base of funded investigators. I would argue that creation of a new R01-like program that tops out at, for example, 6 modules/year, would allow many more researchers access to funding than is currently possible. Ideally, such a program would not be subject to the specialized criteria of R21 and R15 awards, and would be indefinitely renewable, as are current R01s. Such a program could dramatically increase success rates, particularly for early stage investigators, and investigators at smaller institutions.

I wonder to what extent that the lack of scalability is due to whether the PI is hard or soft money funded? A hard salary PI with a grant at $200K/year is going to run close to the same size lab as a PI at ~$400K/year who must pay all salary costs from that grant. Productivity would then be expected similar.

Does this data include issued patents or patent applications that originated from grant-funded research? A plot of # Patents vs. Total Annual Direct Cost would help to isolate the aspect of *utility, applicability and commercial value* of RO1 & PO1 grant funding.

What I find striking about this and the previous data is support for the idea that funding many small laboratories would be more beneficial for the advancement of science than funding fewer, larger laboratories. We in science should learn from business that productivity ought to be normalized (e.g. total impact/funding) rather than absolute (e.g. total impact independent of total funding). As it now stands, laboratories can increase their “productivity” by winning another grant to hire more workers/buy more equipment rather than by achieving more with what they already have.

I am also struck by the bar at 0 publications, which I’m surprised is not higher. As a grant reviewer looking over applicants’ grant histories and publication records, I was often struck how often NOTHING seems to have come out of a previous grant. With all the caveats about what’s a good measure of scientific contribution, we can probably all agree that 0 publications indicates poor productivity. Requiring applicants to show productivity from a previous grant before applying for another one would increase productivity and put the funds in the hands of those who have shown they can turn money into science.