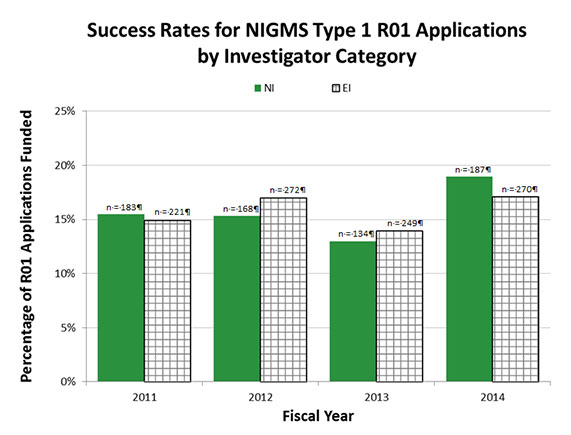

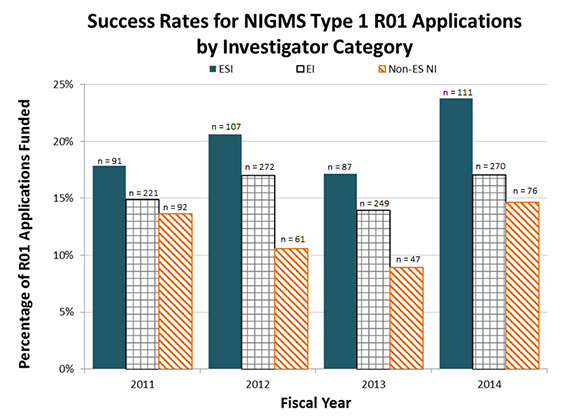

NIH and NIGMS have policies to promote the successful entry of junior investigators into independent biomedical research careers. NIH classifies investigators who have not previously had a major NIH grant into two categories: new investigators (NIs) and early stage investigators (ESIs), a subset of NIs who are within 10 years of completing their terminal research degree or medical residency. The goal of these policies is to support R01-equivalent awards to both of these categories of investigators at success rates (the percentage of new Type 1 R01 applications that were funded) similar to those of established investigators (EIs) who submit new R01 applications.

Given that the NI and ESI policies have been in effect for some time, we wanted to update and extend an analysis of success rates by investigator status performed in 2010 to see if NIGMS has been able to meet these objectives. While we found that the success rates for all NIs were comparable to or greater than that of EIs, our new analysis also revealed that the subset of NIs who completed their terminal research degree at least 10 years ago (non-ES NIs) had consistently lower success rates in obtaining R01s relative to both ESIs and EIs.

We focused our analysis on NIGMS Type 1 R01 applications for Fiscal Years 2011-2014. Figure 1a shows the success rates for EIs and NIs. During the time period analyzed, success rates for both EIs and NIs were comparable. However, when the NIs are separated into ESIs and non-ES NIs, the data show a more nuanced result (Figure 1b). ESIs consistently had higher success rates than either EIs or non-ES NIs when applying for new R01s.

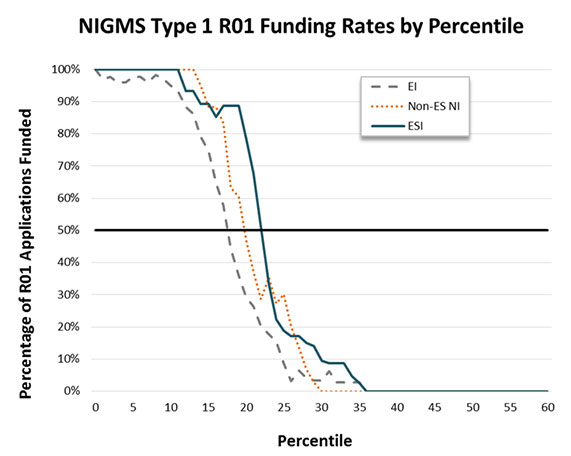

NIGMS has maintained a policy of “reaching” to fund meritorious non-ES NI and ESI applications at higher rates across a range of percentiles; thus, the lower success rates for non-ES NIs were confounding. A graph of the percentage of applications funded by percentile for each investigator category was generated for Fiscal Year 2011, and the evidence of our actions is seen in Figure 2, which shows a rightward shift in the funding curves for applications from non-ES NIs and ESIs relative to the curve for applications from EIs. The patterns for Fiscal Years 2012-2014 paralleled that of Figure 2 (data not shown).

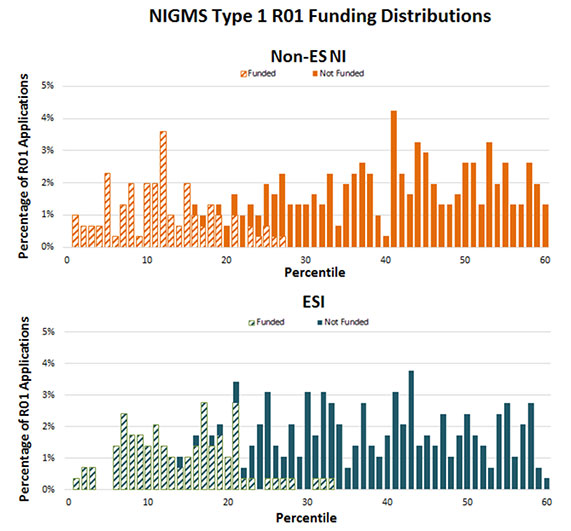

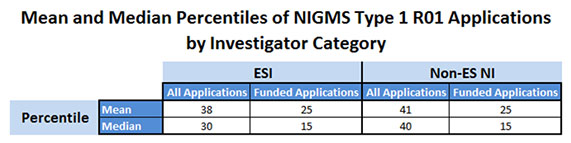

To better understand the difference in success rates for the two categories of NIs, we analyzed their application distribution by percentile. Interestingly, an average of 52% of the non-ES NI applications were unscored over this 4-year period. While this rate was comparable to that of EI applications at 53%, it was moderately greater than that of ESI applications, which was only 40%. The larger number of unscored applications could be one contributor to the lower application success rates for non-ES NIs. Another factor driving down the success rate for the non-ES NI applications appears to be the smaller proportion of scored applications that are funded. On average, only 24.8% of non-ES NI applications that were scored over the time period analyzed were awarded, compared to 32.8% of ESI applications and 33.5% of EI applications. In addition, the distribution of non-ES NI applications is skewed toward the higher percentile range. This result is demonstrated in the funding distributions for Fiscal Year 2011 shown in Figure 3a as well as in the table in Figure 3b, which provides the mean and median percentiles of scored applications from both ESIs and non-ES NIs for Fiscal Years 2011-2014. While the mean and median percentiles for funded applications are equivalent for both investigator categories, the mean and median percentiles for the entire non-ES NI application pool are higher than those for ESIs. This suggests that the non-funded, non-ES NI applications are more heavily skewed toward the higher percentile range.

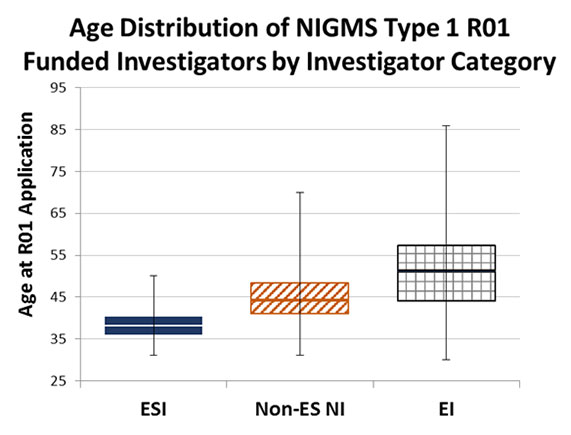

We next looked at the age distribution of NIGMS-funded investigators over the time period analyzed to further understand the difference in age between these groups and to see if there are any trends. While other reports have shown that the median age of first-time R01 grantees is around 42 years, we again found that the distinction between ESIs and non-ES NIs is an important one to make. As Figure 4 shows, there is a significant difference in the age distribution of investigators at the first year of the new award among the three categories. Funded ESIs have a median age of approximately 38 years, while funded non-ES NIs and EIs have median ages of approximately 44 and 51 years, respectively. There is no significant difference between the median ages of those funded and the applicant pool of each category as a whole. This result suggests that there is no bias toward funding a specific population of applicants within each investigator type based on age.

As these data show, NIGMS has supported ESIs at success rates comparable to those of Type 1 applications from EIs, which is consistent with NIH goals. Although the success rates of non-ES NI applications have been lower than those of other investigator types, NIGMS has consistently “reached” to fund applications from non-ES NIs as well. These data bring to light distinctions between the ES-NI and non-ES NI populations and indicate that considering them separately in ongoing monitoring and evaluation at NIGMS is useful.

Acknowledgements

Age data were provided by the Statistical Analysis and Reporting Branch, NIH Office of Extramural Research, and analyzed by the NIGMS Office of Program Planning, Analysis, and Evaluation.

Definitions

New investigator: An individual who has not previously competed successfully as a program director/principal investigator for a substantial NIH independent research award.

Early stage investigator: An individual who is a new investigator and is within 10 years of completing the terminal research degree or medical residency (or the equivalent).

Non-early stage new investigator: An individual who is a new investigator and is beyond 10 years of completing the terminal research degree or medical residency (or the equivalent).

Type 1 application: An application for a new grant.

Success rate: The percentage of new Type 1 R01 applications that were funded.

I continue to fail to see the extended logic of this approach. Yes, I understand that early-stage investigators need a “reach” to accommodate the significant difficulties in adjusting to independent PI status, to establish and recruit people to a laboratory, to generate ample data, and (usually) to make a successful run at tenure (which relies heavily on some funding, the R01 being a stated goal at many institutions). That is a short-term laudable goal with serious negative long-term consequences.

Specifically, the sharp drop-off for established investigators (read: associate and full professors) baffles me. The NIH is involved in creating a pool of tenured professors with a very high rate of funding drop-off as soon as the window of ESI closes. This problem affects the career track, often forcing a newly-tenured investigator to lay off technicians, students, and post-docs, seeking advancement through administration rather than research, and (most terribly) forcing those investigators “off the wagon” (i.e., no funding means no people means no publications means no funding; career ends – once an investigator ends up here, it’s very very difficult to be resurrected). This kills careers, dissuades students, strands postdocs, shutters labs, stifles advancement, ends research programs, removes accumulated expertise from the population of scientists, and creates a gap in continuity as mid-career scientists disappear amid the expensive churn of the new scientists that NIH seeks to “reach” for. To be clear, the proposals submitted by mid- and established-stage investigators are probably no-less good or meritorious, and there are more of them, so a lot of “good” science being proposed is being passed over for funding because it comes from established people. This seems unhealthy in the extreme.

A real solution would be to fund many many more proposals, but tie the level of funding to the score. Highest-ranked proposals could be funded at 100%, 10%-ile at 90%, etc. I guarantee that many people would “make due” with 50% of their asked-for budget, figuring some way to survive with lowered expenses, more efficiency, more-mindful stewardship of NIH’s money, reduced grandiosity, if the alternative is 0% and shutting one’s laboratory.

I also agree with comment #1 by anonymous. Preferential scoring is just setting young investigators up to fail, and at least a dozen new investigators at my institution have done just that. They fail to get their second grant, fail to get tenure, and then end up as investment consultants for venture capital companies, or go to work for their family plumbing business as a logistics coordinator. Word gets out, and discourages a whole next generation from entering science.

Since it’s unacceptable for the system to not fund new investigators, what’s the solution? SUSTAINABLE SCIENCE!

(A) Stop training those you can’t support. It’s a waste of money to train people to do research, when you can’t fund them to do research. Make it much harder to get in to grad school, much harder to finish grad school, and don’t force programs to finish them “on schedule”. This will make more money available for established investigators, and success rates for new investigators will inevitably increase because only those who have demonstrated themselves to be the best over many years will even be competing for grants.

(B) Make a scientific career attractive to intelligent students looking for a challenge. What sane intelligent student would choose to invest 15 years of their lives only to end up in plumbing logistics when their 10th percentile application doesn’t get funded. What sane intelligent student would feel honored and motivated to enter a graduate program that takes students with B+ grade averages and run them through a program with a 90% success rate?

The best minds of the current generation are focused on making you click ads with your mouse – that’s where the challenges and the rewards are for today’s students. That, and maybe plumbing supplies.

I agree with everything said above, as I have experienced and seen the results of this funding system at first hand. One extremely destructive side to all of this is that the system also encourages investigators to leave the bench as soon they can, as so much time is required for writing grant applications. So we end up with senior investigators who are great at writing what should be done, but helpless when they cannot hire workers (often women who have decided it requires too much effort to try to obtain their own funding) to do the actual experiments.

The only thing I do not agree with is using the absolute score to determine overall funding amounts. There are well funded labs, who continue to receive funding even in bad times. These investigators are often extremely free with their spending, ordering expensive equipment they may or may not need and going to meetings* that cost thousands of dollars many times a year, just as examples. Sadly they do not pay their associates any more than labs with less money. They just hire more of them. The system thus encourages a pyramid system with a very wide and unsustainable bottom rung.

The great advantage these investigators have is the freedom to just have someone test out a novel idea. These investigators also have the time (freedom from lab and teaching duties they have hired others to do for them) and the personnel to help them prepare data for and write applications that will score better. This has perpetuated the system of grants as an award for having done great preliminary work, rather than to allow the actual work to be done. Further, because successful funding is the major reason people are appointed to study sections, they also have an inside track there, and name recognition from attending a lot of meetings. So the system is self perpetuating.

I like the R21/R33 concept for introducing and being able to progress with a really novel project. However, most programs that offer this limit the number of grants that can progress to R33 stage, even if the milestones of the first phase are reached. So the success in the R21 phase requires the investigator to re-enter the R01 pool before they have enough data to convince study section members who put them up against those with R01 funding over many years and lab generations.

Re anonymous below, this study section member apparently believe that those doing “exciting science” are the only ones who deserve continued funding. Sometimes “advances” are developing 20 year old science (e.g., combining two pieces of polynucleotide required for a reaction into one). The successful investigators may just know how to spin things better than those who submit ” weak grants” proposing to improve the same system. Further, many investigators are experts in areas that may not seem “sexy” by today’s standards (toxin producing bacteria, for example, or deadly viruses that seem to be very limited in how fast and far they spread) that may not seem relevant to our current health problems. They struggle to survive such reviewers and continue to work with whatever means they can manage to get. These are the researchers who are then called heroes when Anthrax or Ebola epidemics emerge “out of nowhere”.

*re the meetings, many conferences offer nearly free admittance and even travel vouchers to grad students and postdocs. This is used to justify increasing costs for registration at meetings for regular attendees, when the major expense is really what is paid to professional meeting organizers . Often the students chosen to receive these awards come from the very groups who are best funded in the first place. In short, the best funded labs have the best student representation at such meetings as well.

I would like to see a graph of the approval rate as a function of the PIs age. Figure 4 shows EIs with a standard deviation of 30 years above the mean. Perhaps that is a naive use of statistics, but does that mean there are a significant number of PIs between 85 and 95 years of age? Forgive me, but I am suspicious of that number.

Can the NIH show that there is no age discrimination, cutting off funding for older investigators? It is an easy thing to account since they have the applications funded and not funded.

I share with “anonymous” some concerns that what the bonus given to EIs and ESIs may be doing is simply moving back the date at which failure to secure adequate funding occurs. If true, this would further add to the loss of productivity, bang for the NIH buck, and shuttering of labs as described. I would love to see an analysis of how those funded EIs and ESIs fare down the road. Did that jumpstart result in long term gains and a stable laboratory? I don’t know if these programs have been around long enough to provide a large enough dataset for such an analysis but encourage those in charge to plan for it as soon as the data are available.

When I serve on study section, I see that a large percentage of the “New” Investigators that don’t qualify as “Early Stage” are people who have had faculty positions for many years but haven’t been able to land their first R01. I don’t want to over-generalize, but in many cases these are people who either can’t write a good proposal or are doing unexciting science. So as they age out of ES range, they continue to submit weak grants as “new” investigators despite having been trying for many years. It’s not surprising more of these are unscored, and I’m not convinced these types of applications merit the same extra bump given to people who are really just getting their careers started.

Share the same concerns stated by “anonymous” at 3:50pm from personal experience. Being a new non-ESI while not senior enough (associate professor) significantly reduces your chance of getting a R01. Even with good publication record (29 peer-reviewed original research papers during the first NIH funding period, including Cell, multiple Nature xxx), I still have not been able to get an R01 in the past 3 years. Doing experiments and dealing with everything else myself.

Completely agree with #1 anonymous – have seen innumerable investigators fail in their renewal attempts, meaning the initial investment in their first R01 went down the drain. Why is the NIH so proud of this?

N

It is important to note that the analysis we have done here looks only at new grant applications and that a majority of EIs have at least one other NIH grant in addition to the new one they are applying for.

For an analysis of first grant renewal rates, please see Stefan Maas’ post Examining the First Renewal Rates of New NIGMS Investigators. For an analysis of outcomes from new investigator grants, including “reaches,” see Stefan’s follow-up post Further Analysis of Renewal Rates for New and Established Investigator Projects.

Hi John,

I just wanted to congratulate GM for taking the lead among NIH Institutes by carefully analyzing the grant funding issue using actual concrete quantitative metrics. The data do seem to reflect a success rate “fall off” among those non-ESI NIs who have not made it to EI status. With real data in hand, there is actually a basis for coming up with new policy. Rather than NIH policy, which seems to be trying react constructively to the problem, my greater worry is that academic institutions are reacting to short term budgetary pressures rather than trying support their faculty over the long term. Thus, many investigators are not getting the support to adjust their programs to shifting scientific trends and priorities. Unfortunately, I don’t think NIH can fix all of these issues on its own.

It used to be that you needed to renew a grant to get tenure. This meant that not only did the investigator have to be able to write a good grant, but also deliver on what was written in the grant before a tenure decision was made. Now at many institutions all you need to do is get your first grant to get tenure. While on study section I saw ESIs who got a grant as a result of reaching. (Granted I only knew the range not the actual score.) When they resubmitted, or sent in a another new grant they were not able to reach the higher bar set for EIs. This leaves Universities with tenured faculty that cannot support a research program and the departments with a shrinking group of positions occupied by research active faculty. This can lead to a death spiral for specialized or small programs. These are the unintended consequences of the push to fund more junior people. However, if we do not have any junior people funded all research active departments will slowly die for lack of research active faculty. My opinion is the solution to this unintended consequence lies with the universities tenure process, and the solution may be granting associate professor status without tenure until a faculty can show a sustained supported research program. ( Some other institution can go first since this obviously decreases your attractiveness when hiring 😉 Another solution that I like better is increase the NIH budget to a point where we are funding at the 25 percentile.

Thanks for the links to earlier postings with analyses of submission and funding rates for new vs established investigators. I think those data make a compelling case in support of the program that supports new investigators. I encourage continued analyses of longer term outcomes, which I suspect is already underway. And I second the earlier kudos to folks at NIGMS for their ongoing leadership in analyzing and establishing newer programs that address these important issues.

I think the ESI policy greatly affects female scientists who have kids. Even though the non-ESIs who are still NIs have more experience in research than ESIs, it’s so sad to see that it actually reduces their chance of getting an R01. Any applicant at the level of assistant professor would need to be given the same consideration regardless of whether he/she is an ESI or a non-ESI.

It’s important to remember that the policy of “reaching” applies to both ESIs and NIs, and this analysis indicates that NIGMS is doing it for both groups. The data suggest, however, that NIs fare worse in peer review than do ESIs, leading to their lower success rates despite the reaches at the funding decision stage. A finer-grained analysis will be needed to understand whether certain subgroups of NIs are having more trouble in peer review than others.

It’s also important to note that NIH will grant extensions of ESI status for a number of life events and training requirements. More information about ESI status extensions can be found here. For the NI/ESI MIRA pilot, we made both ESIs and NIs at the assistant professor or equivalent level eligible to apply in order to address the concerns you raised.