The doubling of the NIH budget between 1998 and 2003 affected nearly every part of the biomedical research enterprise. The strategies we use to support research, the manner in which scientists conduct research, the ways in which researchers are evaluated and rewarded, and the organization of research institutions were all influenced by the large, sustained increases in funding during the doubling period.

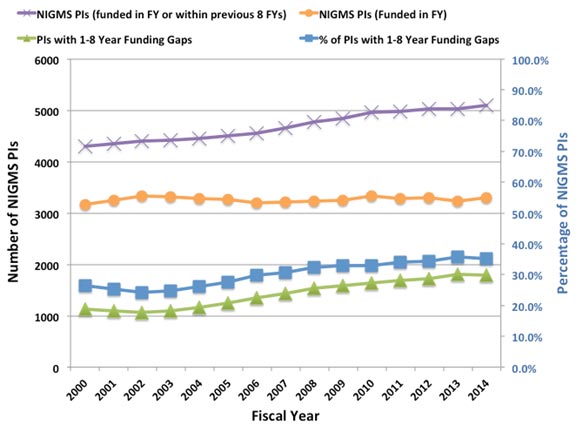

Despite the fact that the budget doubling ended more than a decade ago, the biomedical research enterprise has not re-equilibrated to function optimally under the current circumstances. As has been pointed out by others (e.g., Ioannidis, 2011; Vale, 2012; Bourne, 2013; Alberts et al., 2014), the old models for supporting, evaluating, rewarding and organizing research are not well suited to today’s realities. Talented and productive investigators at all levels are struggling to keep their labs open (see Figure 1 below, Figure 3 in my previous post on factors affecting success rates and Figure 3 in Sally Rockey’s 2012 post on application numbers). Trainees are apprehensive about pursuing careers in research (Polka and Krukenberg, 2014). Study sections are discouraged by the fact that most of the excellent applications they review won’t be funded and by the difficulty of trying to prioritize among them. And the nation’s academic institutions and funding agencies struggle to find new financial models to continue to support research and graduate education. If we do not retool the system to become more efficient and sustainable, we will be doing a disservice to the country by depriving it of scientific advances that would have led to improvements in health and prosperity.

Re-optimizing the biomedical research enterprise will require significant changes in every part of the system. For example, despite prescient, early warnings from Bruce Alberts (1985) about the dangers of confusing the number of grants and the size of one’s research group with success, large labs and big budgets have come to be viewed by many researchers and institutions as key indicators of scientific achievement. However, when basic research labs get too big it creates a number of inefficiencies. Much of the problem is one of bandwidth: One person can effectively supervise, mentor and train a limited number of people. Furthermore, the larger a lab gets, the more time the principal investigator must devote to writing grants and performing administrative tasks, further reducing the time available for actually doing science.

Although certain kinds of research projects—particularly those with an applied outcome, such as clinical trials—can require large teams, a 2010 analysis by NIGMS and a number of subsequent studies of other funding systems (Fortin and Currie, 2013; Gallo et al., 2014) have shown that, on average, large budgets do not give us the best returns on our investments in basic science. In addition, because it is impossible to know in advance where the next breakthroughs will arise, having a broad and diverse research portfolio should maximize the number of important discoveries that emerge from the science we support (Lauer, 2014).

These and other lines of evidence indicate that funding smaller, more efficient research groups will increase the net impact of fundamental biomedical research: valuable scientific output per taxpayer dollar invested. But to achieve this increase, we must all be willing to share the responsibility and focus on efficiency as much as we have always focused on efficacy. In the current zero-sum funding environment, the tradeoffs are stark: If one investigator gets a third R01, it means that another productive scientist loses his only grant or a promising new investigator can’t get her lab off the ground. Which outcome should we choose?

My main motivation for writing this post is to ask the biomedical research community to think carefully about these issues. Researchers should ask: Can I do my work more efficiently? What size does my lab need to be? How much funding do I really need? How do I define success? What can I do to help the research enterprise thrive?

Academic institutions should ask: How should we evaluate, reward and support researchers? What changes can we make to enhance the efficiency and sustainability of the research enterprise?

And journals, professional societies and private funding organizations should examine the roles they can play in helping to rewire the unproductive incentive systems that encourage researchers to focus on getting more funding than they actually need.

We at NIGMS are working hard to find ways to address the challenges currently facing fundamental biomedical research. As just one example, our MIRA program aims to create a more efficient, stable, flexible and productive research funding mechanism. If it is successful, the program could become the Institute’s primary means of funding individual investigators and could help transform how we support fundamental biomedical research. But reshaping the system will require everyone involved to share the responsibility. We owe it to the next generation of researchers and to the American public.

UPDATE: For additional details, read More on My Shared Responsibility Post.

Thank you, Jon, for fostering this important discussion. A few points to consider:

1) It is important not to focus on the number of grants, but on the total award amount. Most of us would love to have one of those >$400K IDC R01s rather than one or two sub-sub modular grants. Don’t penalize PIs who entered the system in the lean years.

2) I don’t quite see how it will work if NIGMS acts unilaterally while it is business as usual in the rest of the institutes. The rest of the NIH budget should also be examined. What about huge intramural budgets? What about the massive grants to clinical centers that fund institutional projects of questionable merit ? Everything should be on the table.

3) The NIH needs to take a hard look at how it evaluates productivity. If NIGMS really places a hard limit on total $$ per lab, that could greatly disadvantage labs who are surviving on NIH money alone versus those who have substantial other sources of funds from internal sources, HHMI, endowed chairs, etc. It is a lot easier to report spectacular progress on your R01 if that work benefited from substantial additional support from other sources. Progress must be evaluated in the context of the complete funding available to the investigator.

I agree with the concern in this post. I am particularly concerned that PIs with many grants may not be as productive per dollar spent as it often seems when grants are reviewed. When I was on a study section many years ago, I noticed that PIs with multiple grants usually had more papers in their progress reports for competitive renewals. I then found that many of those claimed papers acknowledged multiple grants and that some didn’t even acknowledge the grant being renewed but a different grant entirely. This obviously was an unfair advantage compared to PIs with only one grant. I hope that someone is checking this now, but it is a lot of work for a study section member so I am guessing that study sections do not have this information, even if the NIH program director does have it. The problem with that is that study section reviewers just look at the list of publications and are impressed when there are lots of them in good journals, and that unduly improves the priority score. So, to get productivity per dollar into the funding process, NIH really must get this information to the study section before review, and not just for papers that acknowledge multiple GM grants, but for all sources of funding for each published paper that the PI is crediting in the progress report.

The 2010 post of Director Berg found peak productivity at $700K direct per year. So even by this (flawed) measure, *three* grants is still efficient. Yet Lorsch claims thre is the real problem.

How many PIs actually have 4+ awards? What will it do to paylines to place those funds with the people who have 0-2 awards at present? I.e. Will it make a detectable difference?

Jon:

Thank you for sharing this very interesting information and for your continued openness to the perspectives of the research community. FASEB shares your concern about the challenges facing biomedical research in the U.S. and appreciates your pursuit of ways to maximize the productivity of the national investment in research. We have posted our analyses and recommendations online and invite comments as well.

Howard Garrison

As a junior PI, I am acutely aware of productive and truly gifted colleagues in the middle of their independent careers who are going through gap years as your noted in this post. While I am sincerely thankful for the funding I currently have (R01 from NIGMS), I am definitely concerned by the increasing trend in gap years as they disrupt my colleagues established research programs and derail their ability to plan forward. I also appreciate your comment about the need for institutional commitment. I see most academic institutions placing heavy emphasis on the PIs funding status as a measure of their contribution/value. This creates a doubly adverse impact on PIs when they go through gap years in funding. As a junior PI, I can only stay focused on the best possible science that I can do, and hope that both NIH and academic institutions can resolve this impasse in the near future.

Dear Dr. Lorsch,

Thank you so much for verbalizing the concerns that many of us share. You bring up some very interesting points in your blog post. I completely agree that there are some individuals and Institutions that are over-funded to the point of wastage of NIH funds at the expense of smaller labs and individual researchers. I believe that the whole culture of NIH funding, the peer-review process and biomedical research in general will have to change for any meaningful outcomes from the discussion you have so courageously started.

I am a mid-career scientist who lost his R01 funding recently and am currently struggling to keep my lab and research program afloat. So it is likely that many of these comments will sound like the rants of an unsuccessful researcher, but I cannot let this opportunity go to waste without addressing some issues that have bothered me over the years. Instead of speaking in general terms, I will try to address some of the issues using my personal experiences and observations.

The first problem is the peer-review process. You often see PIs being “rewarded” by reviewers for already having lots of funding and publishing in high-impact journals. The assumption of the peer-review process is that all reviewers are evaluating the science and rewarding innovative ideas and good science. But when the PIs ability to attract large grants is used to gauge their chance of success in carrying out the proposed work in the grant being reviewed, then there is something wrong with the evaluation and peer-review process, which needs to be fixed.

Another big issue is the recent spurt of NIH Institutes wanting to fund large consortia or centers. I know that the intentions are good and the idea is to prevent wastage by making resources available to all. But the inadvertent result of these consortia or center grants is the creation of two groups, the haves and the have-nots. Furthermore, by making a few institutions/investigators the gatekeepers of who will be asked to join the consortia and which diseases and disorders will be prioritized, sometimes puts the power in wrong hands.

This would not be such a big problem by itself, but often what happens during peer-review is that reviewers who are not aware of this situation will critique an application by an investigator asking them to approach the said centers instead of asking for funds for individual projects which may or may not fit into the plans of the gatekeepers. This policy often negates the work of several years leaving an investigator scrambling to find alternative ways to continue their work or in the worst case scenario, finding a new research project. This puts them at a further disadvantage because guess what reviewers are going to want when they go in for funding for the newly started project? “A published record in the new field”. This constant pivoting forced by the funding crunch also means that there is no chance for them to become established and be recognized as a “leader” in either the new field or the old. Catch22, anyone?

The other big question is whether the Program staff of NIH Institutes are somehow also perpetuating this culture by encouraging the already highly funded, successful researchers to apply for more NIH funds? I am not saying this is true, but since we are introspecting, I believe that this issue also needs to be looked into and addressed.

At this point, I would also like to address a previous comment which argued against your post and has also been highlighted by FASEB. This individual argued that creative scientists may need more resources to pursue their ideas. I wish that this were true and that the highest funding went to the most creative scientists with the best ideas. Unfortunately, the majority of current funding in biomedical and disease research is focused on incremental analysis rather than “creative science”. Creative and innovative ideas do not usually make it through the peer-review process. Maybe someone should do this analysis to address that issue.

I have a lot more to say, but I might have reached the point at which readers will lose interest in reading further. Thank you again for your post. Your comments are right on and I wish you success in your attempt to change things.

Thanks Dr Lorsch.

Your post must have sent a quake through the empire of the 5% (who control 20% of the funding), leading to the political drums of ‘socialism’. I just want to say that:

NIH is disbursing public funds, and should feel accountable to the public on how it spends and how that benefits the public. The scare drums should be ignored.

Taking the political rhetoric to the front of those who drum the socialism scare, most innovations occur in small, not big companies and businesses. Return on investment is the highest in medium size range.

Given the growing public concerns about credibility in science, the pressure to ‘perform’ in science may be minimized if your proposals are given serious considerations.

Growing big and bigger, when added to ‘performance pressure’ only lead to inefficiencies, killing innovations, and manufacturing ‘science fiction’.

As a long-standing NIH reviewer, I was always struck by the fact that we as reviewers were always told to STRICTLY ignore the budget. Discussing budget was a no. In several study sections, some of us reviewers got around this by saying efficiency of genotyping is part of the scientific evaluation, in effect allowing us reviewers to state that in genomics, cost is part of the scientific merit. But in many cases, “unallowed” comments were of the type: “This is a great proposal, but at $23 Million, it is not better than 10 usual R01s”. Until now such comments were strictly stricken from consideration. That is one mistake – reviewers should consider cost within the merit, especially when, e.g. in genomics, there are orders of magnitude between proposal budgets.

Similarly, internally, $/sqft, $/FTE were proud measures by which schools in Universities measured departments – and the metric was the more the better!

Nobody ever calculated the $/paper IF or other output measures, the lower the better.

In companies, one strives to decrease the $$$/output, NIH funding in US medical schools is about the only area where the incentive is the higher the cost, the better – because of the incentive of indirect costs to the Universities.

So the incentives and the review criteria have to change.

1. Putting a cap on the # of grants a PI can manage smacks of socialism. However, the NIH needs to revise its review of proposals such that having 2 grants funded (say 2 R01s) implies that the PI is 2x more productive than someone with just 1. First, define productivity.

2. Put a cap on the institutional overheads – an overhead of 90+% is ridiculous.

3. Put a cap on the amount that PIs can pay themselves, not just per funded proposal but a total amount. Institutions must contribute to salaries (at least 50%) or leave the federally-funded research business.

Dr. Lorsch, I am excited to see these changes discussed and beginning to be implemented at NIGMS. I agree with essentially all the points you made. Having started my independent academic research career in 1984, I have seen several cycles of boom-bust research funding from NIH. However, the current extremely difficult times, with no sign on major improvement on the horizon, have the potential to cause long term harm to the U.S. biomedical research enterprise. I believe the solutions you propose, particularly if they were adopted by other institutes as well as NIGMS, could help prevent us from losing many biomedical scientists who are early in their graduate education, because they do not want to devote years of training to a career in which talent and hard work often do not translate into long term career success.

I have one other suggestion, really not for NIGMS, but for CSR. I believe it would, if nothing else, increase the perception of fairness in the review process and thereby improve morale among biomedical scientists. As an NIH grant recipient and reviewer, I have observed that the peer review system works well when the task is to distinguish the best 20-25% of the grants, which will then be funded. However, the system does not work well when the task is to choose the best 10% or less. It has long bothered me both as a grant applicant and reviewer that there is really no practical recourse to applicants when reviews contain blatant factual errors or excessively subjective evaluations. Reviewers need to be held accountable for their work. My suggestion would be to send applicants the pre-reviews that will be discussed at the study section meeting and give them a tightly controlled opportunity to address factual errors, cases in which a reviewer overlooked information that was actually included in the application, and subjective opinions that can be easily refuted with additional data or one or two references. This would add very little time to the review process but would motivate reviewers to avoid snap judgements made just to eliminate some outstanding grants in order to make an all out case for the one or two in their stack that they think should be funded (often for subjective reasons such as “importance”, where “importance” is defined as similarity of the grant’s topic to the topic of the reviewer’s research). This process would not change the funding rate, but I believe it would make all concerned feel that the review was fair and that there was an opportunity to address reviewer mistakes, while it still mattered (before final scores are given).

In my opinion, the funding structure is no longer appropriate because we no longer want to grow the number of labs at an exponential pace. Instead, I strongly urge the NIH to consider permanent lab slots that have a decent salary and benefits. While expensive, this would serve multiple purposes: It would give labs an option to find good people for their labs, it would give people who love science but don’t want to run a lab, a place to go. And it would provide continuity for labs, which would help maintain expertise regarding protocols and reagents. This, in turn, would be excellent for training new students and postdocs who enter labs. Funding would need to be at a level of ~0.5-1 per lab, so a sizable population. In reality some labs would have ≥2 and others 0, of course. These grants could be funded by an independent system not the current R01, but more similar to a postdoc fellowship with a little more money and say for 5 years. it could require external funding from the host lab, to be sure people were associated with vibrant research groups.