The doubling of the NIH budget between 1998 and 2003 affected nearly every part of the biomedical research enterprise. The strategies we use to support research, the manner in which scientists conduct research, the ways in which researchers are evaluated and rewarded, and the organization of research institutions were all influenced by the large, sustained increases in funding during the doubling period.

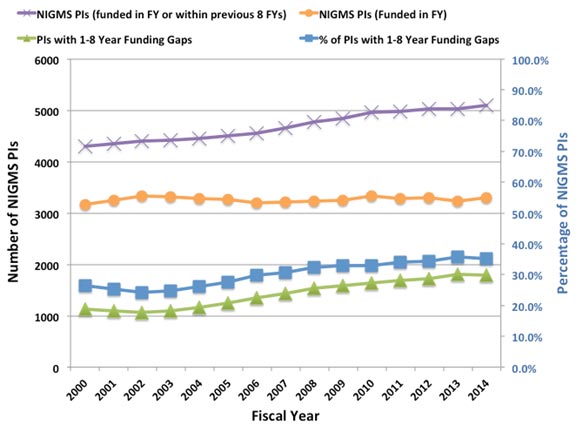

Despite the fact that the budget doubling ended more than a decade ago, the biomedical research enterprise has not re-equilibrated to function optimally under the current circumstances. As has been pointed out by others (e.g., Ioannidis, 2011; Vale, 2012; Bourne, 2013; Alberts et al., 2014), the old models for supporting, evaluating, rewarding and organizing research are not well suited to today’s realities. Talented and productive investigators at all levels are struggling to keep their labs open (see Figure 1 below, Figure 3 in my previous post on factors affecting success rates and Figure 3 in Sally Rockey’s 2012 post on application numbers). Trainees are apprehensive about pursuing careers in research (Polka and Krukenberg, 2014). Study sections are discouraged by the fact that most of the excellent applications they review won’t be funded and by the difficulty of trying to prioritize among them. And the nation’s academic institutions and funding agencies struggle to find new financial models to continue to support research and graduate education. If we do not retool the system to become more efficient and sustainable, we will be doing a disservice to the country by depriving it of scientific advances that would have led to improvements in health and prosperity.

Re-optimizing the biomedical research enterprise will require significant changes in every part of the system. For example, despite prescient, early warnings from Bruce Alberts (1985) about the dangers of confusing the number of grants and the size of one’s research group with success, large labs and big budgets have come to be viewed by many researchers and institutions as key indicators of scientific achievement. However, when basic research labs get too big it creates a number of inefficiencies. Much of the problem is one of bandwidth: One person can effectively supervise, mentor and train a limited number of people. Furthermore, the larger a lab gets, the more time the principal investigator must devote to writing grants and performing administrative tasks, further reducing the time available for actually doing science.

Although certain kinds of research projects—particularly those with an applied outcome, such as clinical trials—can require large teams, a 2010 analysis by NIGMS and a number of subsequent studies of other funding systems (Fortin and Currie, 2013; Gallo et al., 2014) have shown that, on average, large budgets do not give us the best returns on our investments in basic science. In addition, because it is impossible to know in advance where the next breakthroughs will arise, having a broad and diverse research portfolio should maximize the number of important discoveries that emerge from the science we support (Lauer, 2014).

These and other lines of evidence indicate that funding smaller, more efficient research groups will increase the net impact of fundamental biomedical research: valuable scientific output per taxpayer dollar invested. But to achieve this increase, we must all be willing to share the responsibility and focus on efficiency as much as we have always focused on efficacy. In the current zero-sum funding environment, the tradeoffs are stark: If one investigator gets a third R01, it means that another productive scientist loses his only grant or a promising new investigator can’t get her lab off the ground. Which outcome should we choose?

My main motivation for writing this post is to ask the biomedical research community to think carefully about these issues. Researchers should ask: Can I do my work more efficiently? What size does my lab need to be? How much funding do I really need? How do I define success? What can I do to help the research enterprise thrive?

Academic institutions should ask: How should we evaluate, reward and support researchers? What changes can we make to enhance the efficiency and sustainability of the research enterprise?

And journals, professional societies and private funding organizations should examine the roles they can play in helping to rewire the unproductive incentive systems that encourage researchers to focus on getting more funding than they actually need.

We at NIGMS are working hard to find ways to address the challenges currently facing fundamental biomedical research. As just one example, our MIRA program aims to create a more efficient, stable, flexible and productive research funding mechanism. If it is successful, the program could become the Institute’s primary means of funding individual investigators and could help transform how we support fundamental biomedical research. But reshaping the system will require everyone involved to share the responsibility. We owe it to the next generation of researchers and to the American public.

UPDATE: For additional details, read More on My Shared Responsibility Post.

When your chair asks you why you only have two R01s and aren’t submitting new grants, you just tell her, “Hey! I’m sharing responsibility!”

Great post. I really appreciate how NIGMS is trying to deal seriously with these issues.

During these very tight and difficult times for the funding of biomedical research, it is not a surprise that Dr. Lorsch is seeking a rationalization for cutting the size of successful researchers labs down to one or maybe two R01 grants. However, I am very doubtful that any “one size fits all” analysis of funding levels is correct, despite some of the cited papers (one even from Canada, are you kidding?). The truth is that researchers come in many “sizes”, creatively speaking. Very smart and creative scientists may have lots of ideas, most of which merit funding. In turn, they end up with larger groups and more grants. Other researchers may be very good at doing one thing and one thing only, and that is fine, but don’t try to say that everyone should fit that limited mold. In reality, very challenging research problems can require a substantial amount of resources devoted to them. Moreover, some researchers are really very good a multitasking, while some are not. In the end, funding judgements should be made on the creativity of the proposed ideas, as well as the established record of productivity and mentoring by the PI. Anything less is just an excuse to cut one’s budget as a form of “socialism”. If NIH really needs to cut scientists grants during these hard times, then just do it and tell us there is no money, but don’t try to rationalize these decisions by thin arguments that don’t hold water. Yes, there is a level where PI’s “greed” becomes evident (4, 5, or more R01s and certain large center grants), but I think most of these arguments are just an attempt to make budget cuts feel better during hard times. The truth is that the very best who want or need a large group may leave the US for the ETH in Switzerland or a Max Planck Directorship in Germany (or maybe China or Singapore) if this trend continues. It does not help at all to tell best scientists that they would be better scientists if they would just be happy to shrink their groups and live with less funding because we have a bankrupt political system.

This comment is spot on! Socialism in science is doomed to fail. The question to ask is whether one grant to a mediocre lab will advance science more than a second grant to an outstanding and creative lab.

Right on.

Thank you for a thoughtful post and useful reading list, and it will be lovely if all NIH adopts an approach of genuinely involving stakeholders in careful ways of adapting and evolving the medical research industrial complex. I’d urge readers (and leaders) to look at the Letter in PNAS by Kelly and Marians responding to the 2014 piece by Alberts et alia, and keep a cautious skepticism that “reducing hyper-competition back to healthy competition” won’t simply be a matter of doing as the airlines have. In other words, the broader issue is one of a shift in political thinking about the value of public investment for general good (the inflation-adjusted increase in % of GDP allocated to Federally supported research is not very large). Bourne’s Axiom 2 about being wary of top-down management certainly is worth applying to the much-needed evolution. Finally, a consistent and crucial theme is one of transitioning back to a state in which institutions have to invest long-term in their researcher-faculty community. That is vital, but haste makes waste. In the short run, changes in the broader ecosystem of the medical-research-industrial axis have reduced margins terribly. So, the more skin institutions have to put into the game, the less new positions there will be, and that would help ‘reduce competition’ it will not be healthy longer term.

I applaud you Jon Lorsch!

Unfortunately you won’t pull it off, not unless you take off the diplomat hat and don your benign dictator hat. The uber powerful PIs aren’t noble creatures… how do you think they became powerful? Most are egocentric and delusional and they certainly won’t give up their 5+ RO1s without a fight.

The upper tier universities need those indirect cost $$$. You think they won’t bow to the demands of an uber funded PI who threatens to leave? Though they have no problem booting the unfunded Assistant Professor with high teaching scores…

Jon, your heart is in the right place, but this fubar system needs radical change, not more sitting around the table, hoping uber PIs, journals and universities can agree. Start with capping funding for labs at 2 RO1s – don’t ask for permission, just do it, if you can. Then, if you want to be remembered in history, get rid of journals. We pay to submit our papers, which are all political now, then pay to read them. Seriously, wtf??? We should have a central server and all publicly funded research should be published immediately, uncensored, as an online blog, accessible to everyone – this will ensure transparency, efficiency, accountability and reproducibility – 4 things that are severely lost in our current culture.

Best of luck to you, Jon Lorsch – us honest scientists cheer for you!

Hi Jon,

I’ve been present when you have engaged on these difficult questions at meetings, and in those cases you have come across in a better light than how I predict this post would be received. As I know you are aware, the purchasing power of a modular NIH R01 grant has steadily decreased over time, and coupled with NIGMS strategy to keep more investigators funded (which is admirable), a regular NIGMS R01 comes in at ~188,500 direct dollars per year. Given inflation on all levels, doesn’t this suggest that any and all avenues towards efficiency are likely already explored? The greatest and most massive inefficiency in the system is the high probability of a funding gap for NIGMS (and all other Institute) PIs. Given that gaps in funding almost always necessitate laying off staff, and prevent long-term retention of expertise, the great inefficiency here is that expertise cannot possibly be “on demand”. I know that you are also aware that given inflation, the NIH budget never actually doubled. There has likely been a PI bubble, but it is massively deflating with a huge cost.

The lowest quantum for funding units in labs is 1. Paylines are so low, it seems the only way to attempt to prevent a gap in funding is to have an overlap at some point, because going to zero is a massive hit when research needs to grind to a halt. It is difficult to imagine that there is a large number of excessively funded labs.

Thank you for this great post. I can’t agree more on almost all the aspects. Is it possible to reduce the number of big grants and increase the number of smaller grants? Is it possible to ask institutions to share more responsibilities in supporting research and reduce the rate of indirect cost? These funds can instead be used as direct cost to support more research grants. At the same time, we should be careful not to over-produce PhDs and postdocs who are struggling to find permanent positions. Opportunities and necessary training should be provided for PhDs to diversify their career choices in addition to traditional academic jobs. Then brightest young people will be attracted to the STEM fields, and the research enterprise will be more sustainable and productive.

The elephant in the room is those older professors who have tenure, senior-level pay and refuse to retire. A log jam at the university has occurred where bright young minds aren’t even considering NIH-funded professor jobs, why bother when the future is so dire and so competitive just to get an assistant professorship. Additionally our universities have turned into PhD mills where we have a glut of over-educated minds fighting for scraps and 35-40k a year post doc temp positions. Sadly it isnt NIH who should be funding this glut, universities have turned research into big $, it feels like a housing bubble that is now crashing but the bubble is research.

The main difficulty with the doubling was the unwarrented increase in the size of grants. I would recommend an average of about $150,00 to $180,000 as the average award size with a maximum of salary support at 50% between all funding sources (Universities need to step up and actually pay for their faculty). Second, the budget should be reviewed as in the “old days” (pre-1990). In a previous study section in the last five years I have seen essentially no justification for budget (or review) even for some Cambridge, MA labs that requested $650,000 in a single grant. Third, I would suggest making the beginning investigator grant for a 10 year period to allow time for development (and tenure) of junior faculty. At the same time, Universities should rebalance their portfolios so that tuition income is used to more fully support their faculty. This may have the unwanted consequence of shrinking the overall faculty size at a University.

I agree! Thanks Jon for your insightful analysis.

Thank you for this – is goes directly to the heart of the matter and should be required reading for all involved in policy at institutions both at NIH and across the country.

Why is NIH so concerned about ‘buy-in’ from over-funded individuals? They will only change when they’re facing a 30% cut, or an unfunded third grant.

WHY DELAY the broad implement of MIRA and– more importantly– programs to stabilize unfunded PIs and single-RO1 labs?

Do the right things, as soon as possible, to stabilize our diverse research ecosystem.

The idea that NIH should diversify its protfoio by supporting smaller groups is understandable. But exactly the same is applied to the researchers. If a researcher carries just one focused project, she/he is likely to hit a wall and be doomed. The successful strategy is to run several non- or partially overlapping projects, and only one or few would succeed. Therefore “what is good for” NIH may not need necessarily be good for researchers. The other problem is that, in terms of dollar amount, RO1 funding remained at the same level for the past 20 years. Increase RO1 to $1M, and one grant would support an average lab of ~10 people. Current $250K is only good for 2-3 people support and a professor, which is not a competitive set up for the reasons that I outlined above.

Let me speak as a trainee that has benefitted from a T32 slot, a trainee that held an NRSA, an investigator that has been a PI for R01s and for Cores within P awards within academia over a 10+ year period and, more recently, as an investigator that has been a PI on multiple Phase 1, Phase 2 and Phase 1/Phase 2 Fast Track SBIR awards. Let me also throw in the caveat that it is nearly impossible to change the NIH business model because it is reliant on a pie-shaped revenue model with only finite monies at its disposal and there is difficulty running a shop when the entity that provides funding (Congress) has been dysfunctional now for nearly a decade.

In my view, it is the scientists that must adapt into a scientific method and approach that blends basic science, applied science and translational science. Those that will survive need to embrace and seek that blend. We have a blend of these types of science in all of our SBIR-funded programs and we seek collaborations with academia to assist with answering basic science questions.

Perhaps both the traditional funding mechanisms and the peer review can be tweaked to allow and foster such blended science. Perhaps more scientists will found small business concerns to complement their existing efforts. There is certainly a trend toward having new RFAs and PAs to foster such ‘blended’ science; however, more mechanisms rather than less puts more stress and dilution on the pie-shaped funding model.

The NIGMS and the NIH must consider tweaking existing mechanisms of funding and lowering the overall number, seeking to embrace and fund studies that use this blended scientific approach of basic science with applied science with translational science.

Having said all that, the NIH must not abandon its training-based funding because a large swath of the mid-level investigators are gone and there is a threat of losing the new generation of scientists altogether if funding for Ph.D. students and postdoctoral trainees is contracted.

Thank you for the opportunity to comment and I am willing to help brainstorm an implementation of the above.

Even in the best scenario, there are many gaps and potholes in the funding road to try to maintain a decent lab going. As a consequence, a PI is driven to get more and more grants is to build a security buffer to insure the continuity in a high level lab. While intra-mural NIH researchers typically have moderate or small labs, they are judged mainly on their past productivity with a high level of insurance for continuity. In contrast, extra-mural NIH researchers are mostly judged on the “new proposal”, significance, etc, with very little impact from past productivity. There is a disconnect between the goals of NIH and the way the Center for Scientific Review is conducting its study section.

More efficient? My NOA for my R01 came in a few weeks ago for this year, and as usual, it has been cut. I will get ~$181,000 this year. Let’s break down the costs of running a typical (my) lab to illustrate that which is not being considered. I have a fairly normal sized animal colony for my field, because in immunology, nothing gets published well without knockouts and such. That’s $75,000 a year in cage per diem costs. Let’s cover 20% of my salary (with fringe, at 28.5%), one student, and one postdoc (2.20 FTE total). Total salary costs are then $119,800. See, I haven’t done a single experiment and my R01 is gone. How MORE efficient could I possibly be? Even if we cut the animals in half, I have only about $20,000 for the entire year for my reagents. Oh no, you need a single ELISA kit? That’s $800. That doesn’t include plates? Hell, that’s another $300. You need magnetic beads to sort cells, that’s $800 for ONE vial of beads. Wait, that doesn’t include the separation tubes? Another $700 for a pack. You need FACS sort time? That’s $100 an hour. Oh no, it takes 4 hours to sort cells for a single experiment? Another $400. It’s easy to spend $1500 on a single experiment given the extreme costs of technology and reagents, especially when using mice. Then, after 4 years of work, you submit your study (packed into a single manuscript) for publication and the reviewers complain that you didn’t ALSO use these 4 other knockout mice, and that the study just isn’t complete enough for their beloved journal. And you (the NIH) want me to be MORE efficient? I can’t do much of anything as it is.

Anyone running an academic research laboratory should laugh (or vomit) at the mere suggestion that most are not already stretching every penny to its breaking point and beyond.

Thanks, Jon, for this thoughtful post and your excellent efforts to explore alternatives. Referring both to your comments and some subsequent posts, it is unlikely that large private research institutions can support their researchers by increasing average percent salary support. It doesn’t fit a sustainable business model. Since researchers at such institutions need to cover a major part of their own salaries, a single modular R01 can’t suffice. Furthermore, sustainable infrastructure support per lab requires indirect cost recovery from more than one modular R01. In the face of NIH limits in per-person total grant support, such institutions are likely to deem it a financial necessity to drastically decrease the size of their research portfolios … and the only way to do that will be to jettison researchers. If ensuring that more researchers stay active is the goal, I’m not sure that limiting the support per person is the solution. Best success in your efforts.

I think you’ve answered your own question here. Private research institutions are simply an unviable business model in this budget environment. Private investment needs to go up or they should close. It would seem that NIH dollars could go much further in university labs.

This is the greatest news for many PIs who have been struggling for a single R01 for many years.

It is true that BIG funding is not necessarily correlated with Big science as much paradigm-shifitng work came out from accident discoveries. The PIs with big funding normally travel everywhere to be famous or too busy for popularity , how could they really have time to get the first-hand observation, or to sit with their fellows to carefully design the experiments and examine the data? Interestingly but true stories that frequently come out are that many labs are too big, the PIs even could not call the right names for their fellows after the guys/ladies have stayed in their labs for years.

Capping the numbers of R01s will help individual PIs focus on their research and maximize the possibility of success, it is fair for others— Every PI is brilliant in his/her field and has lots of ideas, and want to do many things, but in the rough funding situation, everyone needs to have priority for their research.

In this regard, NIH might learn from NSF where there is limitation for funded proposals (at least in my field, one PI only has one funding). NSF does not have renewal system and every proposal is considered as a new submission. Maybe NIH need to consider this strategy. Also, study section should be more dynamics like NSF.

With regard to “the dangers of confusing the number of grants and the size of one’s research group with success”, I think university faculty and administrators need to re-examine our value system.

Compare two faculty members: Dr. A works 100 hours a week and runs a large research group. Professor B is an at-the-bench scientist who has a single grant and a couple of students or postdocs and is a popular teacher; he/she is also a full partner at home, coaches a kid’s soccer team and is active in a religious or civic organization. Dr. A is more highly valued than Professor B because numbers (dollars, papers, H-index, etc.) are included in evaluations.

We should ask ourselves: is this how it should be? Are these the values we want to pass on to our students?

There is a lot of merit to this plan. However, if this is being pursued unilaterally by NIGMS and not other institutes I wonder if it could have the unintended consequence of steering young investigators away from basic research that would typically be funded by NIGMS. For better or worse, research strategies of top medical schools and research institutes generally seem to be based on the expectation that successful senior scientists will ultimately have the equivalent of 2 or more RO1 grants going at once. If one institute of NIH decides it is not going to support this model, I am guessing that med schools and research institutes will respond by hiring fewer scientists doing research in areas typically supported by NIGMS, which may be perceived as capping investigator funding, unlike other institutes. I point this out without implied criticism.

Dr. Lorsch is right on target with his comments regarding our shared responsibilities. It is clear that re-optimizing the biomedical research enterprise will indeed require major changes in the system and in our attitudes about funding. His many thoughtful comments should be given very serious consideration. In particular, investigators who make a practice of garnering research funds in excess of what they can utilize efficiently are depriving numerous other investigators of their single research grant. It is also important to realize that the sponsoring institutions have to recognize their shared responsibility to support research and not feel that NIH has to bear the entire burden. Some of needed changes will be painful but it is essential that we address the challenges and make the appropriate adjustments before the system collapses and we lose an entire generation of bright young investigators. We need to form a task force and charge them with developing a set of recommendations that will help NIH develop plans to utilize its limited resources with the greatest degree of efficiency and support a broad and diverse research portfolio that maximizes the number of important discoveries. The scientific community should strongly and enthusiastically support the suggestions made by Dr. Lorsch.

I agree with many of Dr. Lorsch’s comments in particular that productivity does not scale and we are losing the breadth in our biomedical research portfolio by not supporting the types of smaller labs that tend to populate smaller medical schools such as mine (SUNY Upstate Medical University). I do wish that that the NIH would come clean concerning their role in the crisis; specifically that to afford new unfunded initiatives, basic science study sections have been fused. This has contributed tremendously to the inordinate impact of flat NIH funding to basic science departments in medical schools to the point now that it is a national crisis. For example, look at the wide range of biology covered in the NCSD study section.

Sincerely,

David Amberg

Vice President of Research

SUNY Upstate Medical University

Jon Lorsch is absolutely right — the responsibility IS shared . . . and so are the problems that result if we don’t take our responsibilities seriously. I spend a good deal of time preaching to old fogies like me, but much of that audience tends to behave as if it is mildly to severely hearing-disabled. Instead, the most important audience for Lorsch’s sermon is young scientists — PhD students, postdocs, young academics, young scientists of every stripe! The reason: these young people will be in charge in just a few years, and right now they have the energy and fresh eyes they need to examine all our problems in a new way. They are not powerless, even though Congressmen, institute directors, and deans are not always disposed to ask their advice. Instead, they can begin by involving themselves in policy initiatives and data-gathering at home — in the lab, in schools, big and small biomedical research centers, wherever. In those settings they need to ask how researchers get evaluated, rewarded, and paid, how choices for different kinds of research goals are made (i.e., by the scientists, by the granting agencies, by institutional officials, other PIs, etc.) . . . and then judge for themselves whether those decisions are being made the way they’d like them to be made 10-15 years from now. In other words, they must ask themselves what kind of scientific world they want to enter and inhabit. Devoting as little as 5% time to such asking/seeking/judging activities now will help to make their scientific futures more fulfilling and fun. Go for it!

One option that I have heard rarely discussed is to link the level of support to the enthusiasm of the reviewers. If the grants getting the very best scores are funded at the full level (or at the level that Council decides is appropriate), while the next tier of scores are unfunded, then we keep punishing research grants in the second tier even though they are often excellent grants that might equally well have gotten a better score in another round. Why not offer some of those PIs the opportunity to accept a smaller award, to keep their labs going, rather than cut them off completely? Smaller could be both a reduced annual budget and a reduced number of years, but I think many labs would be happy to accept such a deal in order to maintain continuity and to generate interesting data for a later re-application.

NIGMS controls the purse strings here. Instead of simply talking, they can put a hard cap on the number of grants a lab can hold. I find it astounding that the number of NIGMS funded investigators has remained flat. There is certainly no evidence of trying to fund PREVIOUSLY FUNDED (not new investigators) who have a funding gap.

Despite the best intentions of New Investigator programs, these have had the unintended consequence of bringing ever more investigators into the system, and simply cutting off their funding supply mid-career. The long term view is that we need to constrain the pipeline and the number of graduate students. But this, of course, conflicts with the well-engrained idea that this cheap labor is required and we need PhDs to support our scientific infrastructure. If they can’t find and maintain research careers, then actually, no we don’t.

1. Can I do my work more efficiently?

2. What size does my lab need to be? How much funding do I really need?

3. How do I define success?

4. What can I do to help the research enterprise thrive?

Jon asks us as members of a community to consider the four important questions above. We should do so. But the questions limit discussion in a rather strict way. Let me propose a parallel set of questions for NIGMS and other agencies to contemplate.

5. How does NIGMS define success? In particular to what extent do the rather narrow bibliometric criteria used in the cited articles represent NIGMS’s definition?

6. How do we measure the value of projects, often labor intensive and hence expensive, that generate products such as software in addition to publications?

7. Is the difficulty in supporting centralized resources such as sequencing and various omics a major contributor to inefficiency?

8. Is there critical research ( as opposed to development) that cannot be deconstructed into R01-sized bites

If NIH were serious about this it could do two things.

1. Slash indirect costs. It is these disbursements that drive the increase in numbers and power of administrators, paying their salaries and those of their support staff, and buying their office furniture. If the indirect costs aren’t there anymore, the pressure from administrators to bring in larger and more grants would decrease. Then tenure and promotion would revert to focusing on quality rather than quantity.

2. Stop supporting graduate students on research grants. Period. Support only U.S. citizens on training grants. In short, stop feeding crowds of young people into the system. Take a leaf our of the American Medical Association’s playbook. When was the last time you heard of a U.S medical school M.D. graduate being unable to get a job in his or her field?

I agree with Dr. Lorsch. The hard part is how to implement this idea in a simple, straightforward way. To do that, I have the following proposal:

The NIH should define two types of major research grants, and decide how much money to allot to each group as a matter of policy:

“R1” grants would be worth $200,000 per year. No PI would be allowed to hold more than one “R1” award at a time, and no more than $40,000 per year could be used to support the PI’s salary. Approximately 70% of NIH money would support these awards.

“R2” grants could be worth up to $300,000 per year. Any PI could apply for as many “R2” awards as he or she desired. Approximately 30% of NIH money would support these awards.

This system would automatically reserve money for a diverse set of smaller labs and new investigators, which is Dr. Lorsch’s goal. This money would be easier to obtain, but would be awarded on a competitive basis to ensure quality. Finally, larger labs would only compete with each other for the the resources to grow.

If this post made many people think on the subject of funding distribution, then it achieved its goal. And to a great degree it did, i think. So, congratulations to Dr. Lorsch. Of course, the best solution is to convince Congress that investing in Science and Education is a one-way road if we want to stay competitive. And subsequently, increase NIH and NSF funding considerably. Until this day comes, other solutions should be implemented. I fully agree that success should not be measured only by the number of grants a PI has received and capping the number of grants any one can have seems like an appealing solution, so more labs can be funded. However, we saw examples above where one grant can not fully fund a lab’s research, so capping the number of grants without increasing their budget is not helping people to succeed. Furthermore, in today’s world, interdisciplinary research has higher chances of getting funded. But interdisciplinary research means that the money on an R01 distributed to multiple PIs and you end up having less money for your lab. How do we factor this in on a “capping rule”? Of course, we can ask for more money, but then the “borderline projects” (nowadays, this means projects on the top 8th percentile) can not be funded. Simplistic scenario. Suppose you are a PO, you have $200K left to spend, one project asks for $400K, another with slightly worse score asks for $250K. Which one you will fund? So I do not think that capping the number of R01s is the way to solve the situation. in any case, it will be nice to see some statistics on how many PIs have more than two grants and how much money are spend on PIs with one, two, etc grants. Capping the percent effort of the PI on all their NIH grants (like NSF?) was also suggested, but this needs a fundamental change in how Schools operate. And unless this is a slow transition, which will allow the Schools to adjust, it will lead to faculty having severe salary cuts and/or loosing their jobs.

I appreciate the concern over how to spend the budget. I think that if we look at Nobel prizes, as one fiducial marker of progress, the key work was usually done with the PI on or near the bench. Basic science, with its translational spin offs, often advances from accidental observations. If the experimental results support the dogma, confidence may change, but no one learns much. We must support small labs where as many people as possible are following their own ideas, not the ideas of others. People unquestionably do the best science when they do their own work.

A major problem with funding is that continued funding without breaks is unlikely and when a lab has to lay off its trained personnel, it may never recover, especially for mid career scientists. Thus, to provide insurance, most investigators that I know try to have at least two grants that are out of phase. If renewal had a good probability with reasonable results, they wouldn’t have to do that.

Efficiency in the labs by the PI is not the issue, the key issue is how NIH spends its money.

The “bandwidth” argument cited by Jon Lorsch identifies a key point in academic research, where training of graduate students and postdoctoral fellows should have a high priority. The biomedical challenges facing our society certainly indicate that a highly skilled professional workforce will be essential in years to come. Individuals with poor or very narrow skill sets as a result of training in a “factory” environment do not represent a good investment in the future. It is remarkable that some high-profile labs seed future research fields with original, talented scientists, while others do not. NIH and universities should consider more than H factors etc. when evaluating impact of funding.

Dr. Lorsch’s comments are perfectly on-target on all points. Unfortunately, the people at the top at universities everywhere (presidents, provosts, deans) are not registering this information and are living in the year 2000. Understandably from their perspective, it is difficult to reconfigure a university system that has arrived at this point over 40 or 50 years.

The short term solution is the obvious giant pink elephant in the room that nobody wants to talk about. Cut indirects drastically! The University built business model is fed off these costs, which truly aren’t necessary at these ridiculous rates (upwards of 100% now!!!) to provide support and overhead to the funded project. What they’ve done is building buildings, pad salaries and allow universities to recruit more and more faculty with no commitment to actually paying for their salaries or financial needs toward their development so long as the indirects keep coming. This then puts pressure on everyone all the way up to the Dean to make sure the cash keeps coming in.

If we are truly serious about fixing the problem, the first step – the one that will have the most impact towards getting more money back to the science, after all that is what NIH is supposed to do- is to rethink the current indirect reality.

I don’t have a dog in this hunt, having moved on from my first R01 from NIGMS to competing for grants from other institutes and other funders. However, I do care about the key role that NIGMS has served providing a catalyst for discovery, a home for small science, and a foundation for independent careers. Even then, with the continuing trend in the disease-focused institutes toward funding translation, RFAs and big science, we need to rely even more on NIGMS to support small scale, investigator-initiated projects and fundamental, mechanistic science in many fields. Despite its growing responsibilities, recent history suggests that NIGMS is not going to be getting a lot more money to distribute and may face continuing tightening, if anything. What to do?

Maintaining the diversity of funded topics and investigators via spreading the investments broadly seems critically important if NIGMS hopes to continue to serve a unique role. If this means that the big labs can no longer get big grants from NIGMS, so be it. They already enjoy a competitive advantage with the other funders including the bigger institutes and foundations and enjoy favored access to donors and institutional support.

So, if someone has to take a new hit in order for NIGMS to be sustainable, it should be the “rich” who are still collecting big grants and high salary recovery. NIGMS has already squeezed the single, modular R01 “middle class” scientists (see your NGA) and grown the ranks of the unfunded “poor” as shown in the figure.

Finally, for my Darwinian/free market friends, the last thing a truly talented and creative scientist should need is a competitive advantage, like a bigger grant. In fact, anyone that good should be able to do more with less. To be fair, don’t we make everyone use the same size racquet and balls and see who wins?

NIH policies of indirect costs incentivize the system, so that Universities are going to push/reward their faculty for bringing in as much money as they can. These costs are not only used to pay expanding administrations, but for the infrastructure itself. For example in California, the 1990 Garamendi legislation allowed universities to use the portion of IDC that normally went to the state, to fund construction loan payments and operation costs for new buildings on campus. At my university the latest, most beautiful building was reserved for high-grant-generating faculty regardless of scientific theme or synergy, not a secret but openly discussed. And if those PIs hope to stay in there, they are expected to continue to produce more funding.

I recently left my tenured full-professorship for a job in Pharma in Europe. I still had NIH and other funding, but it had just become so tiresome to submit so many grants, and still see my lab shrink and become less vibrant than it was when I was an assistant professor. And yes I was extremely efficient and getting more and more papers with less and less money. But with the ever-increasing costs for salaries, benefits, tuition, services, and supplies/reagents at the same time grant awards are decreasing in number and value, at some point it becomes impossible to do good experiments and stay excited about the work.

One real eye-opener about being in Europe is the mandatory retirement age. It is really noticeable, in that younger mid-career scientists get more and more leadership opportunities, and those nearing 65 have a strong motivation to pass on a legacy and coach those coming up behind them before they retire.

It would be great if NIH could put some of their funding toward economic analysis of the research enterprise in the US. NIH could improve their long-term budgeting and improve the predictability of the numbers of applicants in several ways: first by controlling the numbers of incoming graduate students/postdocs by restricting their support to training grants and individual fellowships. Second I think NIH would be well-served to wind down larger grant mechanisms e.g. R01/P01 funding for investigators after the social-security retirement age of 65-67. Finally, IDC should be limited and used only for purposes directly targeted toward supporting investigators research.

I think there are a number of issues that need to be discussed that will help make research dollars go further.

First, for those PIs that do have multiple R01 or equivalent grants, why should institutions get the same amount of indirects on the 3rd and 4th as they do on the 1st? There should be a sliding scale, say NIH should halve indirects for every additional award. This would need to be phased in, as large institutions have become addicted to and dependent on this. However, there was a time when the research enterprise cranked along successfully with researchers hired on 9-month academic contracts and operating on 1 and occasionally 2 R01s. Somehow, academic research (that used to work very well) has become unsustainable for institutions unless NIH pays all of their faculties salaries and forks over millions in indirects. What is different now? This is not a science problem, it is a university administration problem. Individual faculty members can resist pressure (cultural or from chairs) and run a small lab on the budget that they deem appropriate to do their work. That’s what tenure is good for. However, we can’t change the system. NIH and NSF are the only ones with the power to do that.

Second, all the indignant responses about punishing the deserving, successful investigators is kind of ridiculous. At some point, young investigators had to have an intuition, or insight or inspiration, during the conduct of their research. This is what made them good and, in many cases, what made them successful. Large amounts of cash doesn’t foster this, it makes it unnecessary. Ample resources means that judgement doesn’t need to be used, it just enables people to buy further success. It isn’t clear why we should believe that 1 lab with 5 R01s is better than handing an R01 to 4 of the best postdocs from that same lab. Much of the usefulness of the PI in a large lab is knowing how to write grants, knowing how to deal with journal editors, and knowing how to weave bits of data into a sweet-sounding story. It is not primarily their ability to consistently generate the next genius idea: mostly it is about having the resources to jump on and poach new ideas, as they come along.

Imagine everyone getting $200K/year support and 2 technicians and seeing what people could accomplish in 6 years. Are we really supposed to believe that starting from equal footing these 4 and 5 R01 PIs would end up on top again, thereby justifying their present position? Most of them are feeding off the energy and ideas of their bright students and postdocs and wouldn’t recognize the inside of a laboratory. And for the small proportion that really are spilling brilliant ideas; they wouldn’t find a way to pursue these ideas? They couldn’t set aside some time to work at the bench, if they truly felt they had a moment of inspiration?

The ultimate goal should be to get the most science done and make the most progress per dollar. Paying loads of indirects, large faculty salaries and concentrating resources are not the ways to do it.

Dr Lorsch writes: “In the current zero-sum funding environment, the tradeoffs are stark: If one investigator gets a third R01, it means that another productive scientist loses his only grant or a promising new investigator can’t get her lab off the ground. Which outcome should we choose?”

We each approach this question from a different position. If NIH knows which answer is best for its mission, then it should make that choice. To ask large-lab PIs or wanna-be large-lab PIs to voluntarily stop doing what they’re good at doing (getting grants) is silly. I for one agree that a wider base is better for research and that there are limits to the money-begets-more-money model.

I am delighted that Dr.Lorsch at the NIH shares this view on Shared Responsibilities (January 5th, 2015). Unless this translates into NIH-wide policy that trickles down to the SROs and into the peer review criteria, it will have very limited consequences.

I think that Dr. Lorsch’s comments are very important and right on target. Currently there is an imbalance with too many excellent labs getting little or no funding, while some other labs are relatively overfunded and probably not putting the funding to best use. I think we have arrived to this point for several reasons which must be addressed:

1. I believe there was a shift toward larger grants during the Clinton years not only because the money was flowing but also there were insufficient committees to review the small grants. Serving on review committees is hard work and not sufficiently supported and appreciated.

2. I believe that the universities got greedy during the good times and became creative in lobbying for very large institutional funding. Probably they built too many new labs, which are of no use when funding to run the labs is not available.

3. I believe that there was an unfortunate shift at NIH where funding topics were preselected for heavy funding. It is not clear how this happens, but I think that science progresses better and faster with investigator-proposed topics instead of “top-down” selection of topics. Another unfavorable aspect of the “top-down” funding approach is that it created a huge wave of funding for genomic research (DNA-sequencing based) while funding for important basic sciences such as biochemistry, enzymology, physiology, pharmacology, etc. have been left in the dust. Recently I saw an announcement about the sequencing of the Mud Skipper genome. It that really a good way to spend our limited funding?

I believe two R01’s is reasonable but three for one person, or a very large one for one person is no longer tenable. My next door neighbor, who is 70, has a single grant for about $500K and has been grand-fathered into this budget. But it’s really not fair. …. That said, the biggest problem these days, IMHO, is HHMI. Those with HHMI have become the 1% and they throw much of science off kilter because those who do not have HHMI support cannot do science as fast or as big as the HHMI crowd. It has set up two communities, the haves and the have nots, which I believe is dangerous for the future of science. It would be very interesting to see how easy it is to move from one camp into the other, and how location/univ affects that fluidity.

Can you please update us on whatever happened to the recommendation of the Biomedical Workforce Task Force to “initiate discussion with the community to assess NIH support of faculty”? The official NIH website says “A pilot survey was distributed in July 2013. The results of the survey are expected back in the fall of 2013, after which next steps will be determined”.

This issue is highly relevant to the discussion above. At my institution, we are required to generate 70-95% of our salary from grants, depending on the department. Faculty with only a single R01 are told that they must recover their entire salary obligation from the grant, even if it means that there are no funds left to carry out the proposed experiments. This is apparently allowed under current NIH policy.

How many commenters in this thread have proposed/supported a “solution” to the clear and obvious problems with NIH funding that significantly disadvantage themselves, their research operations and their medium term future prospects for funding?

How many have said, in essence, “Do it to Julia! Not me, Julia!”

How many (hi HB) are supporting changes only now, in their dotage, after taking full career-long advantage of the system that led us to this dismal state of affairs?

(apologies to Orwell, of course)

Many great comments here – I particularly would love to see a “bang for the buck” index, provided of course that bang can be objectively quantified.

One key (and rather simple) reform would be to institute a sliding scale for indirect costs. How about full overhead on grant one, 50% of that for grant two; 25% for grant three, etc.

This might help disincentivize the current system, which has led to a pernicious and ultimately self-defeating ponzi scheme of overbuilding of capacity.

I agree with many of the comments in this post. I applaud Jon Lorch for making the issue an open one, from the perspective of the funding agency, and starting a conversation. The thing is we ARE facing a crisis–right now, real people with talent and promise and a lot to give society (and who represent tax payer investment) are falling through the cracks–losing labs, jobs in science etc. I mean, the crisis is here–it’s not just a future abstraction. So it makes no ethical or practical sense to have a very few large labs with tremendous resources while many strong and often younger people that have helped these same labs reach success have nothing. It’s a poor use of our resources and we have to think about new models for allocation to promote both good science and a healthy scientific infrastructure. The hard questions are how do we fix this while maintaining meritocracy, and Jon is correct, one thing we must ask is “What is a good scientist?” I like Jon’s ideas for trying to address this question, and have a modest one to add. Is is possible that some centers, or tools and “common use” services could be centralized in a few strong locations and made accessible to smaller research labs? So instead of every lab or even every university having to support its own mouse colony(ies), as an example, there could be a few centers for this type of work? This is just an example & I don’t know if it would work, but it seems we have a lot of duplicate effort going on at universities and institutions that we don’t necessarily need (though the caveat is that the current system of ‘duplication’ supplies local jobs and local control, which I am sure has some advantages…). What about expensive clinical trials for drug testing? How big is NIH’s investment in these types of trials, through funding projects at university med schools, for example?…these are often very high risk, expensive ventures and rarely lead to fundamental “conceptual” breakthroughs, which should be the focus of academic science. And when they work who enjoys the profits? Does the tax-payer patient get a cheaper drug? (I doubt it) Does the NIH (the taxpayer) get a large chunk to reinvest in basic research? (I doubt it). Or does Big Pharma make a killing (most likely). Surely, private drug companies should not make all the profits if they haven’t taken the risk of a large investment but instead have let NIH (the tax-payer) face the risk.

Dear Dr. Lorsh,

Are you really suggesting that researchers that have 4 and 5 grants relinquish voluntarily their control of the system by decreasing the number of grants they have? Really? This is like asking Walmart to increase voluntarily the salaries of its employees above minimum wage. Are you also asking Universities to change the way they do business? Really? Because of NIH funding, high indirect cost and ridiculously high salary recoveries requested from researchers, Universities have been expanding almost without limits to capture more NIH money. The administrators at the top are getting huge economic incentives based on the money they bring in grants.

By the way, NIH has the power to buffer this funding problem. Simply, limit the salary recovery imposed on the faculty by Universities to 50%, reduce the indirect cost to 40% across the board, and make investigators that apply for a third or fourth grants to compete with each other for funding using a specific pool of funds. Finally, stop initiatives, such the translational research program, that most of us think have no major benefits and are utilizing a significant amount of resources.

I imagine that the implementation of some of these solutions would put, at least initially, many Universities that thrive on getting NIH funds in a difficult economic situation. However, if we consider that the Universities are “too big to fail” the rest of the research community will be the one failing.

Once place to start on redistribution NIH funds to greater productivity is to stop paying indirect costs on the PI’s salary

I think the essential element to most of these comments is that there is not a shared responsibility for initiating change. It is up to NIH to reform the system. If NIH feels that a broader distribution of funds is better and healthier for science, they need to take action and mandate it. Those with the most to lose from a transition to a more equitable system are the labs with massive amounts of funding. So, if NIH is waiting for them to self-regulate or for them to support this, you will be waiting forever. The same holds true for universities. They are not going to act with regard to what’s best for science or their faculty; they will suck as much money out of the system as NIH will let them get away with. Asking them to do otherwise is like asking JP Morgan or Goldman-Sachs to pretty-please behave ethically. The question is whether the mission of NIH is biomedical research and progress, or is it to further the ambitions of administrators at Stanford and Harvard. If it is the former, then the Institutes have to decide what is best for that mission and act soon.

Wonderful blog, Dr. Lorsch, which has elicited many excellent comments.

Bochner’s points 1 and 3 are right on target. (1) NIH’s review process is highly stressed. An advantage of spreading out grant money would mean a larger, more diverse reviewer pool. (3) NIH needs to reduce the top-down approach and revert to more investigator driven science.

Indirect is a huge issue. Consider funding based on total requested dollars.

I strongly second Harvey’s post. The at bench researcher with few grants who contributes to society outside of research work is being weeded out.

To answer your direct questions. I need 1-2 grants (R01’s or similar from other funding institutions). To have a vibrant scientific environment, I need at least two other people to work with directly, (but they don’t need to be funded 100% by my grants) and I need surrounding PI’s who are funded. I constantly try to improve my efficiency. I help the research enterprise by reviewing papers and proposals (NIH and others), volunteering in the public schools, and when I have the opportunity mentoring younger scientists.

Signed – unfunded, mid-career researcher

Dear Dr. Lorsch:

To begin with I am in complete concurrence with your views on the need for rethinking of how we distribute the limited grant funding currently supported by taxpayers dollars. Small academic research operations are fundamental to both the present and future of science. These operations not only develop new ideas and directions in science, but also are the pipeline and defining entity of the next generation of scientists that will be tackling the medical and environmental crises that inevitably will surface as nature and evolution reloads. Please keep in mind, the future of science is not the assistant professors, postdocs or even the graduate students out there performing research today. They are the present of science. The future of scientific research discovery are those yet to be identified and motivated young undergraduates still deciding on what they want to be when they graduate. These students get their inspiration and early introduction to science through the smaller generally single grant operations found in most state and private universities throughout this country. Therefore, it stands to reason that as these smaller operations flounder so will the quality and quantity of talented research scientists necessary for tackling the next set of curves nature throws at us. Unfortunately, this is not a problem for future generations but a very real one in our current environment. Due to the poor job market and interest in scientific research, we basically have to now import the majority of our postdocs and graduate students. This may work in the short run, but as the economy flounders one would have to expect that this source of talent will begin to disappear also.

Having said that, I am not clear on how the concept of “Shared Responsibility” will resolve these issues. The idea of limiting the number and size of grants, although in no way original, is long overdue. This is a good start, but I think there are several other belt-tightening measures that might also be introduced. They include:

1. Perhaps the most abused and controversial waste of NIH resources in the extramural research funding sector is in the indirect cost allocations. I would be willing to bet that no investigator getting a 2nd or even a 3rd grant, double their indirect cost requirements. This is simply gravy for the institutions and a source of grant funding being misused. Why not reduce indirect costs (e.g. by 50%) on any 2nd and 3rd grants.

2. Pay closer attention to abuses in the grant direct cost areas. For example, the College at the state institution I was a professor at requested that all faculty ask for salary reimbursement on their grants. On the surface this is a reasonable request, but looking closer at it one notes that most of these faculty had their salary paid through the state, but the funds received for salary reimbursement were not returned to the state. Furthermore, this salary reimbursement program was incentivized by the establishment of an “award” or salary bonus based primarily upon the salary reimbursement dollars brought in through one’s grants. I feel certain we were not alone in such misuse of direct cost grant funds. A more rigorous monitoring/justification of direct cost expenses such as these might substantially increase available funding for other competitive grant applications.

3. Do away with the Program Project and RFA system. These systems, although good in concept, in practice they are simply another avenue for funding less competitive grants.

4. Finally, there is the NIH Intramural program. The stories of waste there are numerous.

These are simply 4 ideas for which I am sure there are many others. They require shared sacrifices by both the granting institutions and the grant recipients. If this is what you were referring to when you said “Shared Responsibility”, then I am all for it.